Nueva España

STORY OF FILIPINAS part VI

\\\\\\\\\\\\\\\\\\\\\\\\\\\\\\\\\\\\\\\\\\\\\\\\\\\\\\\\\\\\\\\\\\\\\\\\

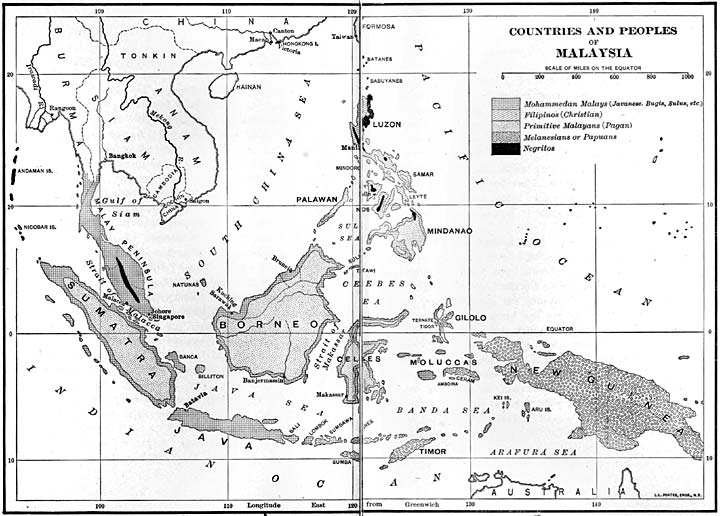

Origin of the Race.—It is thought that the Malayan race originated in southeastern Asia. From the mainland it spread down into the peninsula and so scattered southward and eastward over the rich neighboring islands. Probably these early Malayans found the little Negritos in possession and slowly drove them backward, destroying them from many islands until they no longer exist except in the places we have already named.

The Malayan peoples are of a light-brown color, with a light yellowish undertone on some parts of the skin, with straight black hair, dark-brown eyes, and, though they are a small race in stature, they are finely formed, muscular, and active. The physical type is nearly the same throughout all Malaysia, but the different peoples making up the race differ markedly from one another in culture. They are divided also by differences in religion. There are many tribes which are pagan. On Bali and Lombok, little islands south of Java, the people are still Brahmin, like most inhabitants of India. In other parts of Malaysia they are Mohammedans, while in the Philippines alone they are mostly Christians.

The Wild Malayan Tribes.—Considering first the pagan or the wild Malayan peoples, we find that in the interior of the Malay Peninsula and of many of the islands, such as Sumatra, Borneo and the Celebes, there are wild Malayan tribes, who have come very little in contact with the successive civilizing changes that have passed over this archipelago. The true Malays call these folk “Orang benua,” or “men of the country,” Many are almost savages, some are cannibals, and others are headhunters like some of the Dyaks of Borneo.

In the Philippines, too, we find what is probably this same class of wild people living in the mountains. They are warlike, savage, and resist approach. Sometimes they eat human flesh as a ceremonial act, and some prize above all other trophies the heads of their enemies, which they cut from the body and preserve in their homes. It is probable that these tribes represent the earliest and rudest epoch of Malayan culture, and that these were the first of this race to arrive in the Philippines and dispute with the Negritos for the mastery of the soil. In such wild state of life, some of them, like the Manguianes of Mindoro, have continued to the present day.

Tribes of Mindanao.—In Mindanao, there are many more tribes. Three of these tribes, the Aetas, Mandaya, and Manobo, are on the eastern coast and around Mount Apo. In Western Mindanao, there is quite a large but scattered tribe called the Subanon. These people make clearings on the hillsides and support themselves by raising maize and mountain rice. They also raise hemp, and from the fiber they weave truly beautiful blankets and garments, artistically dyed in very curious patterns. These peoples are nearly all pagans, though a few are being gradually converted to Mohammedanism, and some to Christianity. The pagans occasionally practice the revolting rites of human sacrifice and ceremonial cannibalism.

All through the central islands, Panay, Negros, Leyte, Samar, Marinduque, and northern Mindanao, are the Bisaya, the largest of these peoples. At the southern extremity of Luzon, in the provinces of Sorsogon and the Camarines, are the Bicol. North of these, holding central Luzon, Batangas, Cavite, Manila, Laguna, Bataan, Bulacan, and Nueva Ecija, are the Tagálog, while the great plain of northern Luzon is occupied by the Pampango and Pangasinan. All the northwest coast is inhabited by the Ilocano, and the valley of the Cagayan by a people commonly called Cagayanes, but whose dialect is Ibanag. In Nueva Vizcaya province, on the Batanes Islands and the Calamianes, there are other distinct branches of the Filipino people, but they are much smaller in numbers

Early Contact of the Malays and Hindus.—These people at the time of their arrival in the Philippines were probably not only of a higher plane of intelligence than any who had preceded them in the occupation of the islands, but they appear to have had the advantages of contact with a highly developed culture that had appeared in the eastern archipelago some centuries earlier.

Early Civilization in India.—More than two thousand years ago, India produced a remarkable civilization. There were great cities of stone, magnificent palaces, a life of splendid luxury, and a highly organized social and political system. Writing, known as the Sanskrit, had been developed, and a great literature of poetry and philosophy produced. Two great religions, Brahminism and Buddhism, arose, the latter still the dominant religion of Tibet, China, and Japan. The people who produced this civilization are known as the Hindus. Fourteen or fifteen hundred years ago Hinduism spread over Burma, Siam, and Java. Great cities were erected with splendid temples and huge idols, the ruins of which still remain, though their magnificence has gone and they are covered to-day with the growth of the jungle.

Hindu Culture on the Malayan Peoples.—This powerful civilization of the Hindus, established thus in Malaysia, greatly affected the Malayan people on these islands, as well as those who came to the Philippines. Many words in the Tagálog have been shown to have a Sanskrit origin, and the systems of writing which the Spaniards found in use among several of the Filipino peoples had certainly been developed from the alphabet then in use among these Hindu peoples of Java.

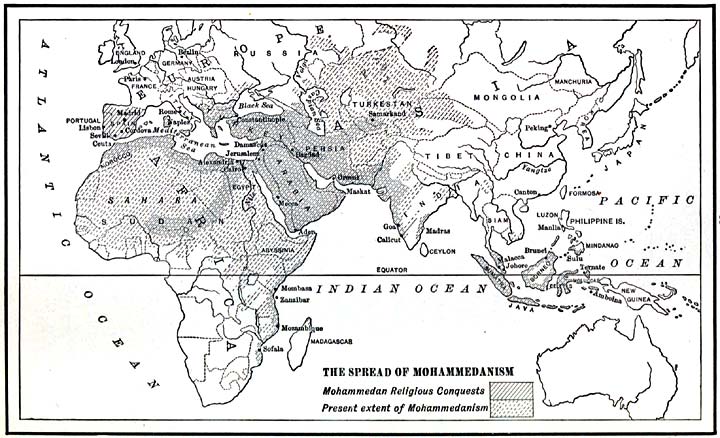

Spread of Mohammedanism to Africa and Europe.—The armies of Arabian horsemen, full of fanatical enthusiasm to convert the world to their faith, in a century’s time wrested from Christendom all Judea, Syria, and Asia Minor, the sacred land where Jesus lived and taught, and the countries where Paul and the other apostles had first established Christianity. Thence they swept along the north coast of Africa, bringing to an end all that survived of Roman power and religion, and by 720 they had crossed into Europe and were in possession of Spain. For nearly the eight hundred years that followed, the Christian Spaniards fought to drive Mohammedanism from the peninsula, before they were successful.

At that time the true Malays, the tribe from which the common term “Malayan” has been derived, were a ]small people of Sumatra. At least as early as 1250 they were converted to Mohammedanism, brought to them by these Arabian missionaries, and under the impulse of this mighty faith they broke from their obscurity and commenced that great conquest and expansion that has diffused their power, language, and religion throughout the East Indies.

The Mohammedan Population of Mindanao and Jolo owes something certainly to this same Malay migration which founded the colony of Borneo. But the Maguindanao and Illano Moros seem to be largely descendants of primitive tribes, such as the Manobo and Tiruray, who were converted to Mohammedanism by Malay and Arab proselyters. The traditions of the Maguindanao Moros ascribe their conversion to Kabunsuan, a native of Johore, the son of an Arab father and Malay mother. He came to Maguindanao with a band of followers, and from him the datos of Maguindanao trace their lineage. Kabunsuan is supposed to be descended from Mohammed through his Arab father, Ali, and so the datos of Maguindanao to the present day proudly believe that in their veins flows the blood of the Prophet

The Tartar Mongols.—Then in the thirteenth century all northern Asia and China fell under the power of the Tartar Mongols. Russia was overrun by them and western Europe threatened. At the Danube, however, this tide of Asiatic conquest stopped, and then a long period when Europe came into diplomatic and commercial relations with these Mongols and through them learned something of China.

Marco Polo Visits the Great Kaan.—Several Europeans visited the court of the Great Kaan, or Mongol king, and of one of them, Marco Polo, we must speak in particular. He was a Venetian, and when a young man started in 1271 with his father and uncle on a visit to the Great Kaan. They passed from Italy to Syria, across to Bagdad, and so up to Turkestan, where they saw the wonderful cities of this strange oasis, thence across the Pamirs and the Desert of Gobi to Lake Baikal, where the Kaan had his court. Here in the service of this prince Marco Polo spent over seventeen years. So valuable indeed were his services that the Kaan would not permit him to return. Year after year he remained in the East. He traversed most of China, and was for a time “taotai,” or magistrate, of the city of Yang Chan near the Yangtze River. He saw the amazing wonders of the East. He heard of “Zipangu,” or Japan. He probably heard of the Philippines.

In 1398 came the furious and bloody warrior, the greatest of all Mongols,—Timour, or Tamerlane. He founded, with capital at Delhi, the empire of the Great Mogul, whose rule over India was only broken by the white man. Eastward across the Ganges and in the Dekkan, or southern part of India, were states ruled over by Indian princes.

China was great and prosperous under the Mings. Commerce flourished and the fleets of Chinese junks sailed to India, the Malay Islands, and to the Philippines for trade. The Grand Canal, which connects Peking with the Yangtze River basin and Hangchau

The Chinese seem to have been much less exclusive then than they are at the present time; much less a peculiar, isolated people than now. They did not then shave their heads nor wear a queue. These customs, as well as that hostility to foreign intercourse which they have to-day, has been forced upon China by the Manchus. China appeared at that time ready to assume a position of enormous influence among the peoples of the earth,—a position for which she was well fitted by the great industry of all classes and the high intellectual power of her learned men.

The Malay Archipelago.—If now we look at the Malay Islands, we find, as we have already seen, that changes had been effected there. Hinduism had first elevated and civilized at least a portion of the race, and Mohammedanism and the daring seamanship of the Malay had united these islands under a common language and religion. There was, however, no political union. The Malay peninsula was divided. Java formed a central Malay power. Eastward among the beautiful Celebes and Moluccas, the true Spice Islands, were a multitude of small native rulers, rajas or datos, who surrounded themselves with retainers, kept rude courts, and gathered wealthy tributes of cinnamon, pepper, and cloves. The sultans of Ternate, Tidor, and Amboina were especially powerful, and the islands they ruled the most rich and productive

Between all these islands there was a busy commerce. The Malay is an intrepid sailor, and an eager trader. Fleets of praos, laden with goods, passed with the changing monsoons from part to part, risking the perils of piracy, which have always troubled this archipelago. Borneo, while the largest of all these islands, was the least developed, and down to the present day has been hardly explored. The Philippines were also outside of most of this busy intercourse and had at that date few products to offer for trade. Their only connection with the rest of the Malay race was through the Mohammedan Malays of Jolo and Borneo. The fame of the Spice Islands had long filled Europe, but the existence of the Philippines was unknown.

\\\\\\\\\\\\\\\\\\\\\\\\\\\\\\\\\\\\\\\\\\\\\\\\\\\\\\\\\\\\\\

Hispaniola was made the center from which the Spaniards extended their explorations to the continents of both North and South America. On these islands of the West Indies they found a great tribe of Indians,—the Caribs. They were fierce and cruel. The Spaniards waged a warfare of extermination against them, killing many, and enslaving others for work in the mines. The Indian proved unable to exist as a slave. And his sufferings drew the attention of a Spanish priest, Las Casas, who by vigorous efforts at the court succeeded in having Indian slavery abolished and African slavery introduced to take its place. This remedy was in the end worse than the disease, for it gave an immense impetus to the African slave-trade and peopled America with a race of Africans in bondage.

The Voyage of Hernando Magellan.—In the mean time a way had at last been found to reach the Orient from Europe by sailing west. This discovery, the greatest voyage ever made by man, was accomplished, in 1521, by the fleet of Hernando Magellan. Magellan was a Portuguese, who had been in the East with Albuquerque. He had fought with the Malays in Malacca, and had helped to establish the Portuguese power in India.

n the 20th of September, 1519, Magellan’s fleet of five ships set sail from Seville, which was the great Spanish shipping-port for the dispatch of the colonial fleets. On December 13 they reached the coast of Brazil and then coasted southward. They traded with the natives, and at the mouth of the Rio de la Plata stayed some days to fish.

The weather grew rapidly colder and more stormy as they went farther south, and Magellan decided to stop and winter in the Bay of San Julian. Here the cold of the winter, the storms, and the lack of food caused a conspiracy among his captains to mutiny and return to Spain. Magellan acted with swift and terrible energy. He went himself on board one of the mutinous vessels, killed the chief conspirator with his own hand, executed another, and then “marooned,” or left to their fate on the shore, a friar and one other, who were leaders in the plot.

==================================

Latroni islamds

The Ladrone Islands.—Their relief must have been inexpressible when, on coming up to land on March the 7th, they found inhabitants and food, yams, cocoanuts, and rice. At these islands the Spaniards first saw the ]prao, with its light outrigger, and pointed sail. So numerous were these craft that they named the group las Islas de las Velas (the Islands of Sails); but the loss of a ship’s boat and other annoying thefts led the sailors to designate the islands Los Ladrones (the Thieves), a name which they still retain.

The Philippine Islands.—Samar.—Leaving the Ladrones Magellan sailed on westward looking for the Moluccas, and the first land that he sighted was the eastern coast of Samar. Pigafetta says: “Saturday, the 16th of March, we sighted an island which has very lofty mountains. Soon after we learned that it was Zamal, distant three hundred leagues from the islands of the Ladrones

Homonhón.—On the following day the sea-worn expedition, landed on a little uninhabited island south of Samar which Pigafetta called Humunu, and which is still known as Homonhón or Jomonjól.

It was while staying at this little island that the Spaniards first saw the people of the Philippines. A prao which contained nine men approached their ship. They saw other boats fishing near and learned that all of these people came from the island of Suluan, which lies off to the eastward from Jomonjól about twenty kilometres. In their life and appearance these fishing people were much like the present Samal laut of southern Mindanao and the Sulu Archipelago.

Limasaua.—Pigafetta says that they stayed on the island of Jomonjól eight days but had great difficulty in securing food. The natives brought them a few cocoanuts and oranges, palm wine, and a chicken or two, but this was all that could be spared, so, on the 25th, the Spaniards sailed again, and near the south end of Leyte landed on the little island of Limasaua. Here there was a village, where they met two chieftains, whom Pigafetta calls “kings,” and whose names were Raja Calambú and Raja Ciagu. These two chieftains were visiting Limasaua and had their residences one at Butúan and one at Cagayan on the island of Mindanao. Some histories have stated that the Spaniards accompanied one of these chieftains to Butúan,

On the island of Limasaua the natives had dogs, cats, hogs, goats, and fowls. They were cultivating rice, maize, breadfruit, and had also cocoanuts, oranges, bananas, citron, and ginger. Pigafetta tells how he visited one of the chieftains at his home on the shore. The house was built as Filipino houses are today, raised on posts and thatched. Pigafetta thought it looked “like a haystack.”

It had been the day of San Lazarus when the Spaniards first reached these islands, so that Magellan gave to the group the name of the Archipelago of Saint Lazarus, the name under which the Philippines were frequently described in the early writings, although another title, Islas del Poniente or Islands of the West, was more common up to the time when the title Filipinas became fixed.

Cebu.—Magellan’s people were now getting desperately in need of food, and the population on Limasaua had very inadequate supplies; consequently the natives directed him to the island of Cebu, and provided him with guides

Leaving Limasaua the fleet sailed for Cebu, passing several large islands, among them Bohol, and reaching Cebu harbor on Sunday, the 7th of April. A junk from Siam was anchored at Cebu when Magellan’s ships arrived there; and this, together with the knowledge that the Filipinos showed of the surrounding countries, including China on the one side and the Moluccas on the other, is additional evidence of the extensive trade relations at the time of the discovery.

Cebu seems to have been a large town and it is reported that more than two thousand warriors with their lances appeared to resist the landing of the Spaniards, but assurances of friendliness finally won the Filipinos, and Magellan formed a compact with the dato of Cebu, whose name was Hamalbar.

Death of Magellan.—And now follows the great tragedy of the expedition. The dato of Cebu, or the “Christian king,” as Pigafetta called their new ally, was at war with the islanders of Mactán. Magellan, eager to assist one who had adopted the Christian faith, landed on Matán with fifty men and in the battle that ensued was killed by an arrow through the leg and spear-thrust through the breast. So died the one who was unquestionably the greatest explorer and most daring adventurer of all time. “Thus,” says Pigafetta, “perished our guide, our light, and our support.” It was the crowning disaster of the expedition.

The Fleet Visits Other Islands.—After Magellan’s death, the natives of Cebu rose and killed the newly elected leader, Serrano, and the fleet in fear lifted its anchors and sailed southward from the Bisayas. They had lost thirty-five men and their numbers were reduced to one hundred and fifteen. One of the ships was burned, there being too few men surviving to handle three vessels. After touching at western Mindanao, they sailed westward, and saw the small group of Cagayan Sulu. The ]few inhabitants they learned were Moros, exiled from Borneo. They landed on Paragua, called Puluan (hence Palawan), where they observed the sport of cock-fighting, indulged in by the natives.

From there, still searching for the Moluccas, they were guided to Borneo, the present city of Brunei. Here was the powerful Mohammedan colony, whose adventurers were already in communication with Luzon and had established a colony on the site of Manila. The city was divided into two sections, that of the Mohammedan Malays, the conquerors, and that of the Dyaks, the primitive population of the island. Pigafetta exclaims over the riches and power of this Mohammedan city. It contained twenty-five thousand families, the houses built for most part on piles over the water. The king’s house was of stone, and beside it was a great brick fort, with over sixty brass and iron cannon. Here the Spaniards saw elephants and camels, and there was a rich trade in ginger, camphor, gums, and in pearls from Sulu

Hostilities cut short their stay here and they sailed eastward along the north coast of Borneo through the Sulu Archipelago, where their cupidity was excited by the pearl fisheries, and on to Maguindanao. Here they took some prisoners, who piloted them south to the Moluccas, and finally, on November 8, they anchored at Tidor. These Molucca islands, at this time, were at the height of the Malayan power. The ruler, or raja of Tidor was Almanzar, of Ternate Corala; the “king” of Gilolo was Yusef. With all these rulers the Spaniards exchanged presents, and the rajas are said by the Spaniards to have sworn perpetual amnesty to the Spaniards and acknowledged themselves vassals of the king. In exchange for cloths, the Spaniards laid in a rich cargo of cloves, sandalwood, ginger, cinnamon, and gold. They established here a trading-post and hoped to hold these islands against the Portuguese.

As a matter of fact, 180 degrees west of the meridian last set by the pope extended to the western part of New Guinea, and not quite to the Moluccas; but in the absence of exact geographical knowledge both parties claimed the Spice Islands. Portugal denied to Spain all right to the Philippines as well, and, as we shall see, a conflict in the Far East began, which lasted nearly through the century. Portugal captured the traders, whom El Cano had left at Tidor, and broke up the Spanish station in the Spice Islands. The “Trinidad,” the other ship, which was intended to return to America, was unable to sail against the strong winds, and had to put back to Tidor, after cruising through the waters about New Guinea.

Walang komento:

Mag-post ng isang Komento