DARK AGES

during the time

of the lost civilization of the roman empire

THE STORY OF THE THIRD TRIBE

Across the wide plains of Northern India, attempting to re-people it with the men of olden time, historical insight fails us at about the seventh century during the fall ofRome resulted to decadence.. Almost everything in the known world stopped...

there were no more business dealings,Most of the people live smal communities.. because most of the large towns an cities were destroyed by the barbarians.... No more schools.. almost all people became ignorant The only remaining instituion that kepp the people moving were the churches. Most people live arond the church....This was what happened in the west

BUT INTHE EASTERNWORLD LIFE CONTINUED

THROUGH THE ARABS 0 BY THE ABBASID DYNASTY OF BAGHDAD

THEN CHINA STARTED ITS CIVILIZATION FOLLOWED BY INDIA....

the World was still there, though, at the time, far back as B.C. 2000, the voices of Aryans who have lived and died are still to be heard

The Punjâb floods unbroken to the very foot of the hills, may gain from it an idea of the wide ocean whose tide undoubtedly once broke on the shores of the Himalayas.

The same eye may follow in fancy the gradual subsidence of that sea, the gradual deposit of sand, and loam brought by the great rivers from the high lands of Central Asia. It may rebuild the primeval huts of the first inhabitants of the new continent--those first invaders of the swampy haunts of crocodile and strange lizard-like beasts--but it has positively no data on which to work. The first record of a human word is to be found in the earliest hymn of the Aryan settlers when they streamed down into the Punjâb.

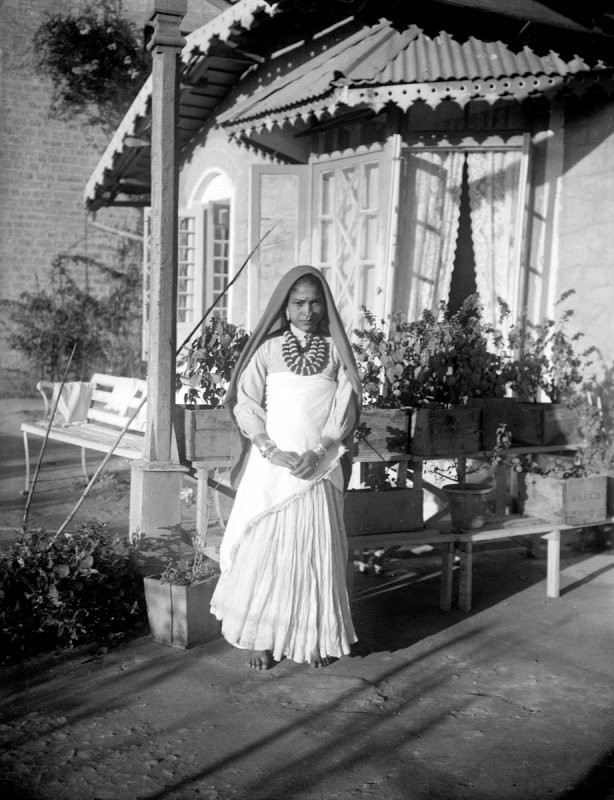

It is not only that these Aryan invaders were themselves in a state of civilisation which necessarily implies long centuries of culture, of separation from barbarians; but besides this, they found a people in India civilised enough to have towns a disciplined people, who invented tools; women whose ornaments were of gold, poisoned arrows whose heads were of some metal that was iron.

All this, and much more, is to be gathered in the aboriginal inhabitants of India. Naturally enough, as inevitable foes, they are everywhere mentioned with abhorrence, with the impression of a "tawny race who utter fearful yells."

Who, were these people?

Aryan Pandâvas

Certain it is that for long centuries the reddish or tawny Dâsyas managed to resist the white-skinned Aryas, so that even ain the great war of Mâhâbhârata--that is, some thousand years later than --they struggle was still going on. n those days the Aryan Pandâvas dispossessed an aboriginal dynasty from the throne of Magadha. The new dynasty belonged to the mysterious Nâga or superior Serpent race, and they followed the path of Alexander's invasion of India found some satrapies still held by the remnants of the Seleucids

It is impossible, to avoid wondering whether the Aryans really found the rich plains of India a howling wilderness peopled by savages close in culture to the brutes, or whether, in parts of the vast continent at least, they found themselves pitted against another invading race, a barbarians whodestroyed the ARoman Empire the Goths, Simmerians Dacians the Huns from the north-east as the Aryan hails from north-west?

So the story is told. These Dâsyas, "born to be cut in twain," have yet the audacity to have different dogma, conflicting canons of the law. Even in those early days religion was the great unfailing cause of living.

THE TIME OF MAHABRATA

B.C. 2000 TO B.C. 1400

"Land of the Five Rivers," iNDIA rivers were counted as seven. That is to say, the Indus was called the mother of the six--not five--streams which, as now, joined its vast volume. In those days this juncture was most probably in comparatively close proximity to the sea. Of these six rivers only five remain: the Jhelum, the Chenâb, the Râvi, the Beâs, the Sutlej. The bed of the sixth river, the "most sacred, the most impetuous of streams," which was worshipped as a direct manifestation of Sarâswati, the Goddess of Learning, is still to be traced near Thanêswar, where a pool of water remains to show where the displeased Plunged into the earth and dispersed herself amongst the desert sands.

The stream never reappears; but its probable course is yet to be traced by the colonies of Sarâswata Brahmans, who still preserve, more rigidly than other Brahmans, the archaic rituals of the Vedas. The reason for this purity of rite being, it is affirmed, the grace-giving quality of Mother Sarâswati's water which, with curious quaint cries, is drawn in every village from the extraordinarily deep wells (many of which plunge over 400 feet into the desert sand), at whose bottom the lost river still flows.

Into this Land of the Seven Rivers, then, came---wanderers who describe themselves as of a white complexion. That they had straight, well-bridged noses is also certain. To this day, as Mr Risley the great ethnologist puts it, "a man's social status in India varies in inverse ratio to the width of his nose"; that is to say, the nasal index, as it is called, is a safe guide to the amount of Aryan, as distinguished from aboriginal blood in his veins. One constant epithet given to the great cloud-god Indra--to whom, with the great fire-god Agni, the vast majority of the hymns in the Rig-Veda are addressed--is "handsome-chinned." But the Sanskrit word sipra, thus translated "chin," also means "nose"; and there can be no doubt that as the "handsome-nosed" one, Indra would be a more appropriate god for a people in whom, that feature was sufficiently marked to have impressed itself, as it has done, on countless generations

When the Aryans came a matter still under dispute. That they were a comparatively civilised people is THAN THE DâsyasTHEY TOOK TO ORGANIZE THE NATIVES , of the cultivation of corn, of ploughing, and sowing, and reaping.

Practically Indian agriculture has gone FOR THE NEXT four thousand years.

Aryan wanderings before India was reached. One of them

begins thus: "Oh! Pushan, the Path-finder, help us to finish our

journey!"

Many kinds of grain were cultivated, but the chief ones seem to

have been wheat and barley. Rice is not mentioned. Animals of all

sorts were sacrificed, and their flesh eaten; and as we read of

slaughter-houses set apart for the killing of cows, we may infer that

the Aryan ancestors of India were not strict vegetarians

It appears to have been the fermented juice of some asclepiad plant

which was mixed with milk. The plant had to be gathered on moonshiny

nights, and many ceremonials accompanied its tituration, and the

expressing of its sap.

So the ancient Aryan rises to the mind's eye as a big, stalwart,

high-nosed, fair-skinned man, with a smile and a liking for

exhilarating liquor, who, after long wanderings with his herds over

the plains of Central Asia--where, reading the stars at night, he sang

as he watched his flocks to Pushan the Path-finder--looked down one

day from the heights of the Himalayas over a fair expanse of new-born

land by the ripples of a receding sea, and found that it was good.

So for many a long year he lived, fighting, ploughing, and

praying--.

Yet the religious feeling of these primitive Aryans was not all tinged by doubt, by sadness; some of their hymns to the Dawn breathe the spirit of deep joy which is in those who recognise,

ABOUT B.C. 1400 TO ABOUT B.C. 1000

The area of India which has now to be considered is much larger. Oudh, Northern Behar, and the country about Benares are comprised in it; but Southern India remains as ever, unknown, even if existent.

Even the remaining Yajur, the Sâma and the Athârva, partake around the -Sanhita , there grew up called Brahmânas,became archaic under the pressure of a greater complexity in life

Brahmânas are but a barren field. Full of elaborate hair-splitting, cumbered with elaborate regulations for the performance of every rite; prolix, prosy, they reflect only a religion which was fast breaking down into canonical pomposity. It is true that towards the end of the Epic period matters improved a little, and in the teachings of the Ûpanishads--last of the so-called "revealed Scriptures" of India--we find a very different note; but as these seem to belong, by right of birth, more to the Philosophical period which follows on the Epic, we will reserve them for subsequent consideration

theGREAT WAR..........................................

Warrior from the Kauravas

strong tribe called Bhâratas or Kurus who had settled near Delhi did for long years struggle with another strong tribe called the Panchâlas, who had settled near Kanauj, is more than likely. With this background, then, of truth, the story of the Mâhâbhârata is a fine romance, and throws incidentally many a side-light on Hindu society in these remote ages. But it is prodigiously long. In the only full English translation which exists it runs to over 7,500 pages of small type. Anything more discursive cannot be imagined. The introduction of a single proper name is sufficient to start an entirely new story concerning every one who was ever connected with it in the most remote degree. But it is a treasure house of folk-lore and folk tales, interspersed, quaintly, by keen intellectual reasonings on philosophical subjects, and still more remarkable efforts to pierce the great Riddle of the World by mystical speculations. It is, emphatically, in every line of it, fresh to the uttermost. It is the outcome of minds--for it is evidently an accretion of many men's imaginations--that still felt the first stimulus of wonder concerning all things, to whom nothing was common, nothing impossible.

Pandavas

Pandavas

To most critics this main thread presents itself as a prolonged war between the Kaurâvas and their first cousins the Pandâvas--in other words, between the hundred sons of Dhritarâshta, the blind king, and the five sons of his brother Pându--but to the writer the leit motif is the story of Bhishma. It is a curious one; in many ways well worthy of a wider knowledge than it has at present in the West.

Bhishma, then, was the heir of Shantânu, the King of Hastinapûr. His birth belongs to fairy tale, for he was the son of Ganga, the river goddess, who consented to be the wife of the love-struck Shantânu on condition that, no matter what he might see, or she might do, no question should be asked, no remark made. There is therefore a distinct flavour of the world-wide Undine myth in the tale. In this case the lover-husband is of the most forbearing type. It is not until he sees his eighth infant son being relentlessly consigned to the river that he cries: "Hold! Enough! Who art thou, witch?" In consequence of this, in truth, somewhat belated curiosity, the goddess leaves him, after assuring him that her purpose is accomplished. Seven Holy Ones condemned to fresh life by a venial fault have been released by early death, and this last child is his to keep as being, indeed, the pledge of mutual love

====================================

The tribe of Bharatas

a strong tribe called Bhâratas or Kurus who had settled near Delhi did for long years struggle with another strong tribe called the Panchâlas, who had settled near Kanauj, is more than likely. With this background, then, of truth, the story of the Mâhâbhârata is a fine romance, and throws incidentally many a side-light on Hindu society in these remote ages. But it is prodigiously long. In the only full English translation which exists it runs to over 7,500 pages of small type. Anything more discursive cannot be imagined. The introduction of a single proper name is sufficient to start an entirely new story concerning every one who was ever connected with it in the most remote degree. But it is a treasure house of folk-lore and folk tales, interspersed, quaintly, by keen intellectual reasonings on philosophical subjects, and still more remarkable efforts to pierce the great Riddle of the World by mystical speculations. It is, emphatically, in every line of it, fresh to the uttermost. It is the outcome of minds--for it is evidently an accretion of many men's imaginations--that still felt the first stimulus of wonder concerning all things, to whom nothing was common, nothing impossible.

A prolonged war between the Kaurâvas and their first cousins the Pandâvas--in other words, between the hundred sons of Dhritarâshta, the blind king, and the five sons of his brother Pându.

THE KING OF HASTINAPUR

Bhishma, then, was the heir of Shantânu, the King of Hastinapûr. His birth belongs to fairy tale, for he was the son of Ganga, the river goddess, who consented to be the wife of the love-struck Shantânu on condition that, no matter what he might see, or she might do, no question should be asked, no remark made. There is therefore a distinct flavour of the world-wide Undine myth in the tale. In this case the lover-husband is of the most forbearing type. It is not until he sees his eighth infant son being relentlessly consigned to the river that he cries: "Hold! Enough! Who art thou, witch?" In consequence of this, in truth, somewhat belated curiosity, the goddess leaves him, after assuring him that her purpose is accomplished. Seven Holy Ones condemned to fresh life by a venial fault have been released by early death, and this last child is his to keep as being, indeed, the pledge of mutual love.

So far good. Bhishma is brought up as the heir until he is adolescent. Then his father falls in love with a fisherman's daughter who is obdurate. She refuses to marry, except on the condition that her son, if one is born, shall inherit the kingdom. Even a promise that this shall be so is not sufficient for her. She claims that Bhishma must not only swear to resign his own claim to the throne in favour of her son, but must also take a solemn vow of perpetual celibacy, so closing the door against future claims on the part of his children. Devoted to his father, the boy, just entering on manhood, accedes to the proposal; his father marries, and dies, leaving a young heir to whom Bhishma becomes regent. An excellent one, too, as the following extract concerning his regency will show:

"In thOse days the Earth gave abundant harvest and the crops were of good flavour. The clouds poured rain in season and the trees were full of fruit and flowers. The draught cattle were all happy, and the birds and other animals rejoiced exceedingly, while the flowers were fragrant. The cities and towns were full of merchants and traders and artists of all descriptions. And the people were brave, learned, honest and happy. And there were no robbers, nor any one who was sinful; but devoted to virtuous acts, sacrifices, truth, and regarding each other with love and affection, the people grew up in prosperity, rejoicing cheerfully in sports that were perfectly innocent on rivers, lakes and tanks, in fine groves and charming woods

the capital of the Kurus (Hastinapûr), full as the ocean and teeming with hundreds of palaces and mansions, and possessing gates and arches dark as the clouds, looked like a second Amaravati (celestial town). And over all the delightful country whose prosperity was thus increased were no misers, nor any woman a widow, but the wells and lakes were ever full, full were the groves of trees, the houses with wealth, and the whole kingdom with festivities.

Sâtyavâti

A golden age indeed! . And for this, Bhishma the Brother Regent and Sâtyavâti the Queen-Mother.

THE BOY KING

The Boy-King appears to have been but a poor creature. Even Bhishma's famous exploit of carrying off the three beautiful daughters of the King of Benares--Amva, Amvîka and Amvalîka--as brides for the lad, does not seem to have kept him from evil courses.

True, the elder of these three "slender-waisted maidens, of tapering hips and curling hair," cried off the match by bashfully telling the softhearted Bhishma that she had set her affections on some one else; whereupon he, holding that "a woman, whatever her offence, always deserveth pardon," bid her follow her own inclinations. Still the two remaining brides did not avail to prevent the young bridegroom from succumbing to disease, leaving them childless.

Brishma

Brishma

Here, then, was a situation. Bhishma and the Queen-Mother, both of an age, left without an heir! After Eastern TRADITIOn she urges him to take his half-brother's place, and raise up offspring to his father and to herself. But bRISHMA is firm to his oath. "Earth," he says, "may renounce its scent, water its moisture, light its attribute of showing form, yea! even the sun may renounce its glory, the comet its heat, the moon its cool rays, and very space renounce its capacity for generating sound; but I cannot renounce Truth." Pressed to the uttermost he can only reiterate: "I will renounce the three worlds, the empire of heaven, and anything which may be greater than this, but Truth I will not renounce."

Poor Bhishma! One feels that he is , beset by loving women, for when another father for possible heirs is found, Amvîka, who had expected Bhishma, refuses to look at his successor, the result being that her son Dhritarâshta is born blind, and being thus unfitted for kingship, Amvalîka's son Pandu becomes heir to the throne

Hinc illæ lachrymal! Bhishma's vow of celibacy produces the rivals, and his part in the epic henceforward shows but dimly on the bloody background of the long quarrel between the hundred God-given sons of Dhritarâshta, and the five -begotten sons of Pandu.

Yet, overlaid as it is by diffuse divergencies, the story of self-sacrifice, of a man whom all women love and none can gain, goes on. Bhishma, on Pandu's death, installs the blind Dhritarâshta as Regent King, and continues, as ever, faithful to his trust. Once or twice a ring of human pathos, human regret, is heard in the harmony of his good counsels, his unswerving loyalty, his fast determination to "pay the debt arising out of the food which has been given me."

Again, when Amva, the eldest princess of the three maidens whom Bhishma had carried off as brides for his brother, returns in tears from seeking the lover he had allowed her to rejoin, saying that the prince will have none of Bhishma's leavings, there is human regret in the latter's refusal to accept the assertion that the carrying off was equal to a betrothal, and that he is bound in honour to marry the maiden himself! Yet of this refusal comes much. The injured girl calls on High Heaven for requital, and though her champion Râma is unable to conquer the invincible Bhishma, Fate intervenes finally.

Once when Arjuna, third of the five Pandus, climbs up on his knees, all dust-laden from some boyish game, and, full of pride and glee, claims him as father--"I am not thy father, O Bhârata!" is the gentle reply.

Amva's prayers, austerities, find fruit. It was revealed that She was Chikandîni, the daughter of a great king whose wife conceals the child's sex for twenty-one years, until the most valiant of princesell cone,

Bhishma. For among the many confessions of a soldier's faith which the latter here makes is this: "With one who hath thrown away his sword, with one fallen, with one flying, with one yielding, with woman or one bearing the name of woman, or with a low, vulgar fellow--with all these I do not battle." So Chikandîn is beyond Bhishma's retaliation, and when in the final fight he "struck the great Bhârata full on the breast," the latter "only looked at him with eyes blazing with wrath; remembering his womanhood, Bhishma struck him not."

In the course of this war he built a watch-fort at a village called Patali, on the banks of the Ganges, where in after years he founded a city which, under the name of Patâliputra (the Palibothra of Greek writers), became eventually the capital, not only of Magadha, but of India--India, that is, as it was known in these early days

Patali is the Sanskrit for the bignonia, or trumpet-flower; we may add, therefore, to our mental picture of the remaining four Ses-nâga kings, that they lived in Trumpet-flower City

For the rest, two great monarchs, Bimbi-sâra and Ajâta-sutru, must have been near, THEY WERE contemporaries of Darius, King of Persia, who founded an Indian satrapy in the Indus valley. This he was able to do, in consequence of the information collected by Skylax of Karyanda, during his memorable voyage by river from the Upper Punjâb to the sea near Karâchi, thus demonstrating the practicability of a passage by water to Persia. All record of this voyage is, unfortunately, lost; but the result of it was the addition to the Persian Empire of so rich a province, that it paid in gold-dust tribute to the treasury, fully one-third of the total revenue from the whole twenty satrapies; that is to say, about one million sterling, which in those days was, of course, an absolutely enormous sum.

About B.C. 361, or , the reign of the Ses-nâga kings ends abruptly. The dream-vision of the steps of old Râjgrîha with Scythian princelings--parricidal princelings--riding up to their palaces on processional horses, or living luxuriously in Trumpet-flower city, vanishes, and something quite as dream-like takes its place.

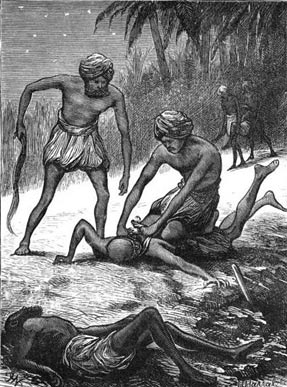

The Nanda dynasty, and the story, if it does nothing else, proves that the family was really of low extraction. That it gained the throne by the assassination of a rightful king, is also certain. But revenge was at hand. The tragedy was to be recast, replayed, and in B.C. 321 Chandra-gûpta, the Sandracottus of the Greeks, himself an illegitimate son of the first Nanda, and half-brother, so the tale runs, of the eight younger ones, was, after the usual fashion of the East, to find foundation for his own throne on the dead bodies of his relations.

But some four years s came to pass, while young Chandra-gûpta, ambitious, discontented, was still wandering about Northern India almost nameless--for his mother was a Sudra woman--he came in personal contact with a new factor in Indian history. It was recalled that on March, B.C. 326, Alexander the Great crossed the river Indus, and found himself the first Western who had ever stood on Indian soil. So, ere passing to the events which followed on Chandra-gûpta's rude seizure of the throne of Magadha, another picture claims attention. of the great failure of a great conqueror

B.C. 620 TO B.C. 327

Scythic hordes invaded India from the north-east, during great war of Kauravas ana Pandavas they met in conflict with the Aryan invaders from the north-west on the wide, Gangetic plains, possibly close to the junction of the Sone River with the Ganges.

There were ten of these kings, Sesu-nâga, Sakavârna, Kshema-dhârman, and Kshattru-jâs, may live again as personalities. At present we must be content with imagining them in their palace at Raja-griha, or "The kings abode surrounded by mountains."

These Ses-nâga princes, their Scythian faces, flat, oblique-eyed, yet aquiline, showing keen under the golden-hooded snake standing uræus-like over their low foreheads, riding up the steep, wide steps leading to their high-perched palaces, on their milk-white steeds; these latter, no doubt, be-bowed with blue ribbons and bedyed with pink feet and tail, after the fashion of processional horses in India even nowadays. Riding up proudly, kings, indeed, of their world, holders of untold wealth in priceless gems and gold--gold, unminted, almost valueless, jewels recklessly strung, like pebbles on a string.

n these days the kingdom of Magadha-- Scythic principality--was entering the l against that ancient Aryan kingdom of Kosâla, of the warriors of these kingdoms joined the great war between the extreme north-west of the Punjâb and Ujjain, in the fifth centurySesu-nâga the king. conquered and annexed the principality of Anga and built the city of New Rajagrîha, which lies at the base of the hill below the old fort. But something there is in his reign grips attention more than conquests or buildings. During his rule, the he foundedf two great religions gave to the world tje teachings of Mâhâvîra and Gâutama Buddha the first teachings of Jainism and Buddhism preached at his palace doors. He is supposed to have reigned for nearly five and twenty years, and then to have retired into private life, leaving his favourite son, Ajâta-sutru, as regent

And here tragedy sets in; tragedy in which Buddhist tradition avers thE Deva-datta, the Great Teacher's first cousin and bitterest enemy, was prime mover. For one of the many crimes imputed to this arch-schismatic by the orthodox, is that he instigated Ajâtasutru to put his father to death.

Whether this be true or not, certain it is that Bimbi-sâra was murdered, and by his son's orders; for in one of the earliest Buddhist manuscripts extant there is an account of the guilty son's confession to the Blessed One (i.e., Buddha) in these words: "Sin overcame me, Lord, weak, and foolish, and wrong that I am, in that for the sake of sovranty I put to death my father, that righteous man, that righteous king."

tradition has it, that death was compassed by slow starvation, the prompt absolution which Buddha is said to have given the royal sinner for this act of atrocity becomes all the more remarkable. His sole comment to the brethren after Ajâta-sutru had departed appears to have been: "This king was deeply affected, he was touched in heart. If he had not put his father to death, then, even as he sate here, the clear eye of truth would have been his."

Walang komento:

Mag-post ng isang Komento