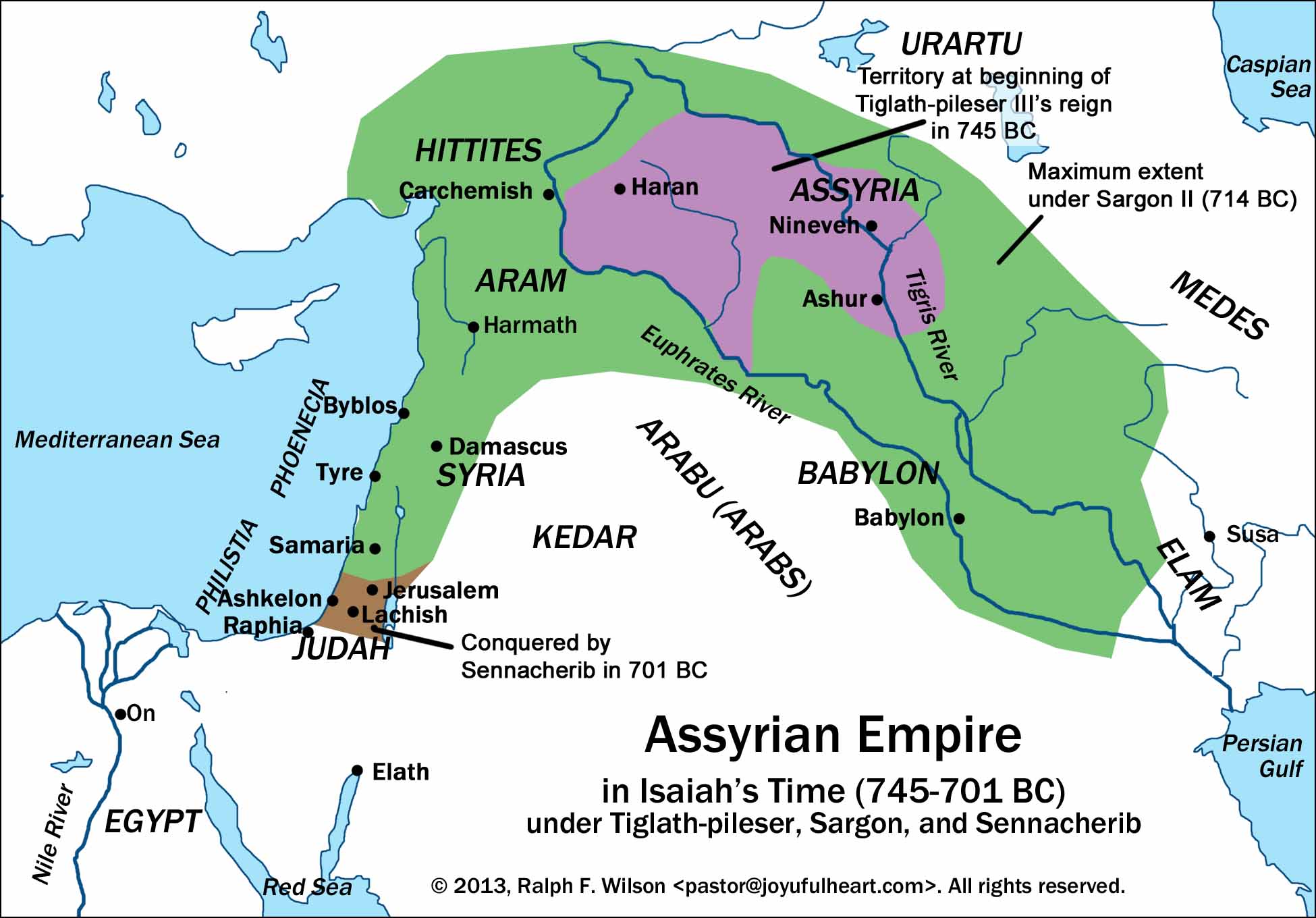

THE FALL OF SAMARIA OF NORTHERN ISRAEL

shalmaneser, king of Assyria

city of samaria was captured by Shalmaneser Army

The fall of Samaria, by Shalmanezer, B.C., 721. From that time history loses sight of the ten tribes, as a distinct people. They were probably absorbed with the nations among whom they settled, to disposethem into inaccessible regions where they await their final restoration. Centuries later They may have been the ancestors of the Christian converts afterward found among the Nestorians. They may have retained in the East territory of Assyria

Persia was once an eastern territory of Assyria

The Jews of the tribes of Judah and Benjamin never entirely departed from their ancient faith, and their monarchs reigned in regular succession till the captivity of the family of David. They were not carried to Babylon for one hundred and twenty-three years after the dispersion of the ten tribes, B.C. 598.

Jewish captives dwell in the remote area

During the captivity, the Jews still remained a separate people, governed by their own law and religion. It is supposed that they were rather colonists than captives, and were allowed to dwell together in considerable bodies—that they were not sold as slaves, and by degrees became possessed of considerable wealth. What region, from time immemorial, has not witnessed their thrift and their savings of money? Well may a Jew say, as well as a Greek, “Quæ regio in terris nostri non plena laboris.” Taking the advice of Jeremiah they built houses, planted gardens, and submitted to their fate, even if they bewailed it “by the rivers of Babylon,” in such sad contrast to their old mountain homes. They had the free enjoyment of their religion, and were subjected to no general and grievous religious persecutions.

----------------------

And some of their noble youth, like Daniel, were treated with great distinction during the captivity. Daniel had been transported to Babylon before Jerusalem fell, as a hostage, among others, of the fidelity of their king. These young men, from the highest Jewish families, were educated in all the knowledge of the Babylonians, as Joseph had been in Egyptian wisdom. They were the equals of the Chaldean priests in knowledge of astronomy, divination, and the interpretation of dreams. And though these young hostages were maintained at the public expense, and perhaps in the royal palaces, they remembered their distressed countrymen, and lived on the simplest fare. It was as an interpreter of dreams that Daniel maintained his influence in the Babylonian court. Twice was he summoned by Nebuchadnezzar, and once by Belshazzar to interpret the handwriting on the wall. And under the Persian monarch, when Babylon fell,

-------------------------

Daniel became a Governor called satrap, with great dignity and power.

Darius king of the Medes destroyed Assyria

FALL OF NINEVEH DESTRUCTION OF ASSYRIAN EMPIRE

When the seventy years' captivity, which Jeremiah had predicted, came to an end, the empire of the Medes and Persians was in the hands of Cyrus, under whose sway he enjoyed the same favor and rank that he did under Darius, or any of the Babylonian princes. The miraculous deliverance of this great man from the lion's den, into which he had been thrown from the intrigues of his enemies and the unalterable law of the Medes, resulted in a renewed exaltation. Josephus ascribes to Daniel one of the noblest and most interesting characters in Jewish history, a great skill in architecture, and it is to him that the splendid mausoleum at Ecbatana is attributed. But Daniel, with all his honors, was not corrupted, and it was probably

through his influence, as a grand vizier, that the exiled Jews obtained from Cyrus the decree which restored them to their beloved land.

The number of the returned Jews, under Zerubbabel, a descendant of the kings of Judah, were forty-two thousand three hundred and sixty men—a great and joyful caravan—but small in number compared with the Israelites who departed from Egypt with Moses. On their arrival in their native land, they were joined by great numbers of the common people who had remained. They bore with them the sacred vessels of the temple, which Cyrus generously restored. They arrived in the spring of the year B.C. 536, and immediately made preparations for the restoration of the temple; not under those circumstances which enabled Solomon to concentrate the wealth of Western Asia, but under great discouragements and the pressure of poverty. The temple was built on the old foundation, but was not completed till the sixth year of Darius Hystaspes, B.C. 515, and then without the ancient splendor.

It was dedicated with great joy and magnificence, but the sacrifice of one hundred bullocks, two hundred rams, four hundred lambs, and twelve goats, formed a sad contrast to the hecatombs which Solomon had offered.

Impoverished, and humiliated Jews, who had returned to the country of their ancestors during the reign of Darius Hystaspes.

XERXES, PERSIAN KING known as Ahasuerus

Esther

It was under his successor, Xerxes, he who commanded the Hellespont to be scourged—that mad, luxurious, effeminated monarch, who is called in Scripture Ahasuerus,—that Mordecai figured in the court of Persia, and Esther was exalted to the throne itself. It was in the seventh year of his reign that this inglorious king returned, discomfited, from the invasion of Greece. Abandoning himself to the pleasures of his harem, he marries the Jewess [pg 111]maiden, who is the instrument, under Providence, of averting the greatest calamity with which the Jews were ever threatened. Haman, a descendant of the Amalekitish kings is the favorite minister and grand vizier of the Persian monarch. Offended with Mordecai, his rival in imperial favor, the cousin of the queen, he intrigues for the wholesale slaughter of the Jews wherever they were to be found, promising the king ten thousand talents of silver from the confiscation of Jewish property, and which the king needed, impoverished by his unsuccessful expedition into Greece. He thus obtains a decree from Ahasuerus for the general massacre of the Jewish nation, in all the provinces of the empire, of which Judea was one. The Jews are in the utmost consternation, and look to Mordecai. His hope is based on Esther, the queen, who might soften, by her fascinations, the heart of the king. She assumes the responsibility of saving her nation at the peril of her own life—a deed of not extraordinary self-devotion, but requiring extraordinary tact. What anxiety must have pressed the soul of that Jewish woman in the task she undertook! What a responsibility on her unaided shoulders? But she dissembles her grief, her fear, her anxiety, and appears before the king radiant in beauty and loveliness. The golden sceptre is extended to her by her weak and cruel husband, though arrayed in the pomp and power of an Oriental monarch, before whom all bent the knee, and to whom, even in his folly, he appears as demigod. She does not venture to tell the king her wishes. The stake is too great. She merely invites him to a grand banquet, with his minister Haman. Both king and minister are ensnared by the cautious queen, and the result is the disgrace of Haman, the elevation of Mordecai, and the deliverance of the Jews from the fatal sentence—not a perfect deliverance, for the decree could not be changed, but the Jews were warned and allowed to defend themselves, and they slew seventy-five thousand of their enemies. The act of vengeance was followed by the execution of

[pg 112]the ten sons of Haman, and Mordecai became the real governor of Persia. We see in this story the caprice which governed the actions, in general, of Oriental kings, and their own slavery to their favorite wives. The charms of a woman effect, for evil or good, what conscience, and reason, and policy, and wisdom united can not do. Esther is justly a favorite with the Christian and Jewish world; but Vashti, the proud queen who, with true woman's dignity, refuses to grace with her presence the saturnalia of an intoxicated monarch, is also entitled to our esteem, although she paid the penalty of disobedience; and the foolish edict which the king promulgated, that all women should implicitly obey their husbands, seems to indicate that unconditional obedience was not the custom of the Persian women

The reign of Artaxerxes, the successor of Xerxes, was favorable to the Jews, for Judea was a province of the Persian empire. In the seventh year of his reign, B.C. 458, a new migration of Jews from Babylonia took place, headed by Ezra, a man of high rank at the Persian court. He was empowered to make a collection among the Jews of Babylonia for the adornment of the temple, and he came to Jerusalem laden with treasures. He was, however, affected by the sight of a custom which had grown up, of intermarriage of the Jews with adjacent tribes. He succeeded in causing the foreign wives to be repudiated, and the old laws to be enforced which separated the Jews from all other nations. And it is probably this stern law, which prevents the Jews from marriage with foreigners, that has preserved their nationality, in all their wanderings and misfortunes, more than any other one cause.

A renewed commission granted to Nehemiah, B.C. 445, resulted in a fresh immigration of Jews to Palestine, in spite of all the opposition which the Samaritan and other nations made. Nehemiah was cup-bearer to the Persian king, and devoted to the Persian interests. At that time Persia had suffered a fatal blow at the battle

of Cindus, and among the humiliating articles of peace with the Athenian admiral was the stipulation that the Persians should not advance within three days' journey of the sea. Jerusalem being at this distance, was an important post to hold, and the Persian court saw the wisdom of intrusting its defense to faithful allies. In spite of all obstacles, Nehemiah succeeded, in fifty-two days, in restoring the old walls and fortifications; the whole population, of every rank and order having devoted themselves to the work. Moreover, contributions for the temple continued to flow into the treasury of a once opulent, but now impoverished and decimated people. After providing for the security of the capital and the adornment of the temple, the leaders of the nation turned their attention to the compilation of the sacred books and the restoration of religion. Many important literary works had been lost during their captivity, including the work of Solomon on national history, and the ancient book of Jasher. But the books on the law, the historical books, the prophetic writings, the Psalms, Proverbs, Ecclesiastes, and the Songs of Solomon, were collected and copied. The law, revised and corrected, was publicly read by Ezra; the Feast of Tabernacles was celebrated with considerable splendor; and a renewed covenant was made by the people to keep the law, to observe the Sabbath, to avoid idolatry, and abstain from intermarriage with strangers. The Jewish constitution was restored, and Nehemiah, a Persian satrap in reality, lived in a state of considerable magnificence, entertaining the chief leaders of the nation, and reforming all disorders. Jerusalem gradually regained political importance, while the country of the ten tribes, though filled with people, continued to be the seat of idolaters..

of Cindus, and among the humiliating articles of peace with the Athenian admiral was the stipulation that the Persians should not advance within three days' journey of the sea. Jerusalem being at this distance, was an important post to hold, and the Persian court saw the wisdom of intrusting its defense to faithful allies. In spite of all obstacles, Nehemiah succeeded, in fifty-two days, in restoring the old walls and fortifications; the whole population, of every rank and order having devoted themselves to the work. Moreover, contributions for the temple continued to flow into the treasury of a once opulent, but now impoverished and decimated people. After providing for the security of the capital and the adornment of the temple, the leaders of the nation turned their attention to the compilation of the sacred books and the restoration of religion. Many important literary works had been lost during their captivity, including the work of Solomon on national history, and the ancient book of Jasher. But the books on the law, the historical books, the prophetic writings, the Psalms, Proverbs, Ecclesiastes, and the Songs of Solomon, were collected and copied. The law, revised and corrected, was publicly read by Ezra; the Feast of Tabernacles was celebrated with considerable splendor; and a renewed covenant was made by the people to keep the law, to observe the Sabbath, to avoid idolatry, and abstain from intermarriage with strangers. The Jewish constitution was restored, and Nehemiah, a Persian satrap in reality, lived in a state of considerable magnificence, entertaining the chief leaders of the nation, and reforming all disorders. Jerusalem gradually regained political importance, while the country of the ten tribes, though filled with people, continued to be the seat of idolaters..

On the death of Nehemiah, B.C. 415, the history of the Jews becomes obscure, and we catch only scattered glimpses of the state of the country, till the accession of Antiochus Epiphanes, B.C. 175, when the Syrian monarch had erected a new kingdom on the ruins of the Persian empire. For more [pg 114]than two centuries, when the Greeks and Romans flourished, Jewish history is a blank, with here and there some scattered notices and traditions which Josephus has recorded. The Jews, living in vassalage to the successors of Alexander during this interval, had become animated by a martial spirit, and the Maccabaic wars elevated them into sufficient importance to become allies of Rome—the new conquering power, destined to subdue the world. During this period the Jewish character assumed the hard, stubborn, exclusive cast which it has ever since maintained—an intense hostility to polytheism and all Gentile influences. The Jewish Scriptures took their present shape, and the Apocryphal books came to light. The sects of the Jews arose, like Pharisees and Sadducees, and religious and political parties exhibited an unwonted fierceness and intolerance. While the Greeks and Romans were absorbed in wars, the Jews perfected their peculiar economy, and grew again into political importance. The country, by means of irrigation and cultivation, became populous and fertile, and poetry and the arts regained their sway. The people took but little interest in the political convulsions of neighboring nations, and devoted themselves quietly to the development of their own resources. The captivity had cured them of war, of idolatry, and warlike expeditions.

During this two hundred years of obscurity, but real growth, unnoticed and unknown by other nations, a new capital had arisen in Egypt; Alexandria became a great mart of commerce, and the seat of revived Grecian learning. The sway of the Ptolemaic kings, Grecian in origin, was favorable to letters, and to arts. The Jews settled in their magnificent city, translated their Scriptures into Greek, and cultivated the Greek philosophy.

Meanwhile the internal government of the Jews fell into the hands of the high priests—the Persian governors exercising only a general superintendence. At length the country, once again favored, was subjected to the invasion of Alexander. After the fall of Tyre, the conqueror advanced to

Gaza, and totally destroyed it. He then approached Jerusalem, in fealty to Persia. The high priest made no resistance, but went forth in his pontifical robes, followed by the people in white garments, to meet the mighty warrior. Alexander, probably encouraged by the prophesies of Daniel, as explained by the high priest, did no harm to the city or nation, but offered gifts, and, as tradition asserts, even worshiped the God of the Jews. On the conquest of Persia, Judea came into the possession of Laomedon, one of the generals of Alexander, B.C. 321. On his defeat by Ptolemy, another general, to whom Egypt had fallen as his share, one hundred thousand Jews were carried captive to Alexandria, where they settled and learned the Greek language. The country continued to be convulsed by the wars between the generals of Alexander, and fell into the hands, alternately, of the Syrian and Egyptian kings—successors of the generals of the great conqueror

On the establishment of the Syro-Grecian kingdom by Seleucus, Antioch, the capital, became a great city, and the rival of Alexandria. Syria, no longer a satrapy of Persia, became a powerful monarchy, and Judea became a prey to the armies of this ambitious State in its warfare with Egypt, and was alternately the vassal of each—Syria and Egypt. Under the government of the first three Ptolemies—those enlightened and magnificent princes, Soter, Philadelphus, and Evergetes, the Jews were protected, both at home and in Alexandria, and their country enjoyed peace and prosperity, until the ambition of Antiochus the Great again plunged the nation in difficulties. He had seized Judea, which was then a province of the Egyptian kings, but was defeated by Ptolemy Philopator. This monarch made sumptuous presents to the temple, and even ventured to enter the sanctuary, but was prevented by the high priest. Although filled with fear in view of the tumult which this act provoked, he henceforth hated and persecuted the Jews. Under his successor, Judea was again invaded by Antiochus, and again was Jerusalem wrested

from his grasp by Scopas, the Egyptian general. Defeated, however, near the source of the Jordan, the country fell into the hands of Antiochus, who was regarded as a deliverer. And it continued to be subject to the kings of Syria, until, with Jerusalem, it suffered calamities scarcely inferior to those inflicted by the Babylonians.

Walang komento:

Mag-post ng isang Komento